By Barbara Carr Whitman

This year’s film MIDWAY has inspired Friends of Midway Atoll to unveil true stories, newly revealed and historical, in the words of those who stood watch, waiting for what most felt was inevitable. Descriptive language comes directly from personal letters, transcripts, historical records and interviews. No footnotes were used so that readers can lose themselves in the story. However, all sources are sited at the end of the story.

The possession of Midway Atoll was crucial for military operations in the Pacific. Due to its location, it was an important trans-Pacific emergency, operations and refueling site.

Much has been written, recorded and documented about the Battle of Midway. However, the heroic events at sea often overshadow what was happening on the islands of Midway from just before the bombing of Pearl Harbor and June 4, 1942 when the Battle of Midway began. This is the story of what happened on Midway between the battles.

LIFE ON MIDWAY BEFORE THE WAR

December 1941: Newly minted US Navy Ensigns Frank Dunlap and George Levin found themselves stationed on a tiny coral atoll. Frank was a communications officer and George was to supervise the maintenance of amphibious bomber planes called PBYs. They were stationed on Sand Island, Midway. Address: Way out somewhere in the middle of the Pacific.

In 1941, Midway felt very exposed to the elements: A salty windswept atoll, encircling two islands, that was stunningly beautiful. The Pacific Ocean lapped turquoise over white coral beaches then turned into its characteristic royal blue further out. Dark patches in glass-clear water indicated where coral reefs dotted the bottom and encircled the atoll boundary.

Jacks, including giant trevally, a fish almost as big as a human, and schools of fluorescent blue trevally patrolled colorful coral reefs dotted with small brightly patterned fish and odd-looking invertebrates. Large goofy dancing birds covered the sandy landscape and filled the sky, making strange screeches and clacking sounds while countless other seabird noises cluttered the air.

It could be called “paradise” or maybe just “another world” but there, life was good. Except for the raising of the flag each morning, which was done with proper military formality, life on Midway was casual and relaxed. Duty hours were 7:00 am until noon, off the rest of the day and off weekends. None of the guys wore shirts in the heat. There was a lot of time but not much to do for recreation except swim in the lagoon and fish.

Even paradise can get routine and lackluster so different activities were planned to fill the gaps. It just so happened that on December 6, 1941, to celebrate finishing a new barracks, the men had “amateur night.” It was fun and boredom was temporarily alleviated with laughter, a few taunts, and lots of smiles. It was a great way to end peacetime, even if they didn't realize it yet.

AND SO IT BEGINS

The morning of December 7th was like all the days before it as the guys awoke to paradise. Many of them were getting ready to go for a swim when early news arrived at 6:30 am that the US Naval base at Pearl Harbor, Island of Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi, a little over 1000 miles away, had been bombed in a surprise attack by the Japanese. Pearl was on fire, ships sunk and lives lost. They learned they had lost at least one battleship – the USS Arizona. It all sounded unbelievable to them but reality set in when war plans were immediately put into effect and those on the ground were told to return to and stay in their barracks.

Five amphibious PBYs (patrol bombers) were already up in the air on routine patrol. Two others were on their way to Wake Island and two were sitting on the seaplane ramp warming their engines in preparation for a rendezvous to lead in a squadron of dive bombers. The planes going to Wake were commanded to return. New search routes were established and aircraft took to the air throughout the day.

About 10:00 am, the ground troops were sent to their positions. There were gun stations and searchlight positions on Sand Island and a communications Command Post in the power station where the generators were. This was the first time the men had been issued live ammo, which they realized indicated something was up, but they still had a hard time grasping the fact that for them World War II had begun.

Regardless of that “unreal” feeling, island residents flew into action. The cooks were told to prepare food that could be sent to the positions. Troops dug foxholes, issued ammunition and scurried about hurrying to complete preparations for battle. Medical supplies were checked and communication systems were confirmed working. Hearts were beating fast.

While all this was happening, two Japanese destroyers were plowing through ocean waters drawing ever nearer. Their mission: To neutralize the air base at Midway thus ensuring a safe return for the Pearl Harbor attack force.

At 6:42 pm one of the marine lookouts on Midway, standing on a platform by his search light at dusk, saw flashes offshore. The destroyers were on their way in. By 9:35 pm, the first shells were flying through the air, constantly moving closer until they struck land.

By freak mischance, a 4.7-inch round went through a ventilation port in the power and communications building which was considered bomb proof. It was made of reinforced concrete 3-6 feet thick with four generators and two boilers on the first floor. The second floor housed the Command Center where Marine Corps First Lieutenant George Cannon had a machine gun command post and telephone switchboard on the concussion deck between two roofs.

Lt. Cannon suffered a crushed pelvis in the attack but made sure his three assistants were evacuated. He refused to go until he had reestablished communications. A few minutes after they got him out, he passed away from his injuries. Two of his assistants that were evacuated earlier were also mortally wounded.

The newly-built seaplane hangar on Sand Island was also shelled. The roof burst into flames but the steel superstructure remained usable. Happily, everyone inside managed to escape. The only casualty was the one PBY that remained inside. The hangar was Ensign George Levin’s duty station. After things calmed down, he and another young officer toasted the beginning of the war they thought inevitable with a shot of rum the other officer had hidden.

WAITING

In the months that followed the December 7th attack, the island was busy with clean up and preparations. Three new runways and a hangar were constructed on Eastern Island. Revetments, chest-high mounds of sand, were built on each side of the runway to protect the planes.

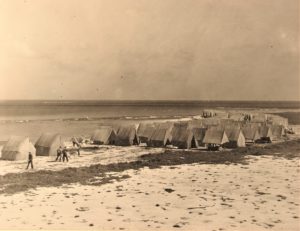

Troops, supplies and equipment poured into Midway by plane and ship. Planes delivered by the USS Saratoga were flown from the ship directly to Eastern Island. Troops and equipment were dropped at Sand Island and barged over. Fuel was brought by barge in 55-gallon drums from Sand Island. It was transferred into a small gas truck which filled the planes. Tents were erected near the runways.

Air crews slept near their planes. All the rest lived at their gun positions in wooden rooms built into holes dug in the sand, then covered with sand. They could go, when permitted, to the new barracks where the kitchen was located to shower and on special occasions when it was safe, men off watch could watch movies inside a blacked out warehouse during the day.

The troops ate two meals a day since most of the men were now living “underground” most of the time and hot food had to be brought to them in food containers by truck. There just was not enough time to, clean dishes, prepare, package and bring three meals a day. They got used to it and it wasn't so bad because every day at noon they were allowed two beers!

Reinforcements arrived in the form of dive bombers, fighter planes and their crews. When the first batch arrived on December 17th, “the men stood on top of their gun emplacements and cheered when the planes droned overhead. The planes represented a real Christmas present.”

Back on Sand Island, Marine PFC John Miniclier was part of the battery responsible for the control station, search lights and sound locators which were pre-radar devices used to detect the location and direction of approaching aircraft. He moved into the damaged power plant with seven other men. They built their quarters with wood and sandbags between the two bombproof roofs. A searchlight was placed on the top deck.

“The sound locator looked like three separated large horns providing information to the control station operator, who used a binoculator to try and see the airplane. The control station operator, when directed could call for illumination and put the beam of light on the target. The antiaircraft guns could use their instrumentation to fire. On Midway these lights had to be installed so they could cover either ships or landing crafts.”

The tower for the control station was built by civilian contractor about 50 yards away. “We put the control unit up there with room for two people, connected the telephone system and a cable to the search light on top of the power plant. The tower needed camouflage and a ladder to go up and down. A 24 hour watch was established and it was my battle station, it was not easy to climb with a helmet and a rifle, but a grand view.”

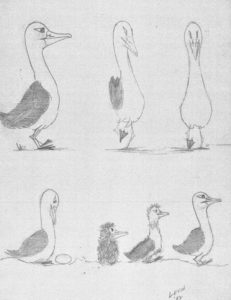

Eventually, “Midway settled into a routine of training and anti-submarine flights, with little else to do except play endless games of cards and cribbage, and watch Midway’s famous albatrosses, in action.”

The “gooney birds” were a source of amusement and many of the men talked to them. The birds had their own runways and took off like airplanes. “They had a runway that ended just short of our barracks, and they didn’t always make it. They crashed, shook it off, and tried again.”

“On Eastern Island, some of the guys caught an albatross, fashioned a metal band for it, and put it on a transport plane going back to Pearl Harbor. They let it go on the tarmac as soon as they got to Pearl Harbor, and the bird hung around a few days to a week. Then it left. It just taxied out and came right back to Eastern Island”.

George Levin loved the albatrosses and spent some of his free time drawing the birds whose antics helped keep spirits high and relieve the pervasive mounting tension. One drawing documented the cycle from courting adults to nest and egg through fledging juvenile. He also carved briar pipes, did other drawings and created a mural which hung in the Officer's Club. He gave his works of creativity to his friends, including Frank Dunlap.

COMFORT FOOD

One of the things the men missed were dairy products. Midway’s “mechanical cow” converted powdered milk into a not very satisfying milk-like product. It was appropriately called KLIM (Milk spelled backwards). George Levin’s family was from a dairy state. When they heard about their son's plight, his parents bought a wheel of cheese, froze it, packed it in sawdust, crated and sent it to him on Midway. When it arrived, the outside had to be pared away but most of it was ready to eat. Frank and a bunch of his companions took care of that in under 24 hours.

TEDIUM WITH A DASH OF EXCITEMENT

A little excitement appeared in the form of a Japanese submarine which intermittently fired upon the island. The routine on Midway was to send out a search plane each afternoon to see if there was any Japanese activity in the area before dark. On almost every Sunday evening, after the recon plane landed, a submarine would surface and fire at Midway. When the Midway batteries returned fire, it submerged.

On one Sunday afternoon after the pattern had been established, two recon planes went up. One landed normally. The other continued to search. The submarine surfaced and fired and the second plane dropped a bomb near it. The sub left and did not return on subsequent Sundays.

Marine Edgar Fox, actually arrived on Sand Island the day of a submarine shelling. “I had been in the Marine Corps for six months. Like others I was green, untested, and so cocky that I wondered why we needed so many of us (fifty-six) to defeat the Japanese….The projectiles from the sub, did not land near our location confirming to us ‘boots' that those Japanese couldn't hit a barn wall if they were inside the barn. I was later to learn how foolish that notion was.”

Private Fox's duty station was a “pillbox” and he lived in an attached camouflaged underground room constructed with sides and top made of railroad ties and a coral sand floor. He and his bunker mate had to stoop to walk in and out. Not surprisingly, there was a constant moisture problem. Shoes were kept high and dry and duty clothes hung on nails. The rest of their issued clothes, shoes and underwear were stored in the barracks and they changed when they went back there for showers. There were two bunks across from each other and a light bulb that was so low wattage, they joked that they “had to turn on a flashlight to see if the bulb was lit”. An outhouse, which they had cleverly constructed to collapse when not in use to avoid detection, was situated behind the dune that covered the bunker and his “Midway Suite”.

He writes: From January to June we marines patrolled the beach in front of our guns one hour before sun down till one hour after sunrise. During the days we tweaked our wire defenses, removed birds from the barbwire stretched around the entire island.

During this period I was a Private First Class assigned to a Special Weapons Platoon with an assignment to deny enemy access to the real estate in front of my gun. I was not permitted to wander about the island without permission. Mail was censored, certain areas were off limits. No one had a camera. Most of us welcomed the Japanese surfacing and shelling us….ah boredom, put on a back burner.

The last reported submarine attack before the battle began was on February 10, 1942. In his customary obtuse way Ensign Frank Dunlap, who as communications officer was probably privy to information the general troops were not, wrote his uncle on February 20th:

Dear Unc, Sorry to have been so long in writing to you but we have been pretty busy. . . About myself there is really little or nothing to report except that I am fine although very tired of this same hunk of sand but it looks as if there is some sort of change looming in the not too distant future.

ANTICIPATION

For months, it was unknown where the Japanese would strike next, the Aleutian Islands or Midway Atoll. On May 2nd, Admiral Nimitz traveled to the atoll to determine its defensive readiness and ascertain needs. Immediately thereafter, war supplies and men started to arrive at the island. Rumor was that a strike would come in July.

Ships carrying troops, guns, a tank, Dauntless bombers, Wildcat fighter planes and 22 pilots, most fresh out of flight school, flowed in. B-26 Marauder bombers, specially rigged to carry torpedoes, and 12 additional PBY Catalinas showed up. “There was such a concentration of planes in the air that the birds were forced to stay on the ground.”

On May 28th the Japanese armada began steaming its way toward Midway with four aircraft carriers, 11 battleships, 23 cruisers, 65 destroyers and several hundred fighters, bombers and torpedo planes.

Midway troops and a few civilians that had volunteered to stay on the island, were now prepared as best they could be for an attack by the largest and most powerful naval fleet in the world at that time.

The question was, when would they arrive? The answer came May 30th, when everyone on Midway received this communique.

IMPENDING ATTACK FORCES Information available indicates that the Japanese plan an all-out attack on Midway with a view to its capture. The attack may start any hour now. Our job is to hold Midway…Be alert and on your toes. Don’t unnecessarily expose yourself or fire prematurely. Keep cool. There will be a lot of banging and booming, but don’t let this confuse you. In a battle, the odds may seem to be against you for a time, and things may appear to be going badly for our side, but always remember, the enemy is in a worse fix than you. A torpedo, bomb or shellfire may sink a ship or boat, but our islands will still be here when it is all over.

Midway’s pilots began searching for the Japanese immediately. Excited and scared at the same time, the troops waited, unsure of the future, always on alert. All recreational activities were suspended and “the boys” started to realize that “this was the real deal”.

“The beaches were sown with home-made mines consisting of ammunition boxes filled with dynamite and 20-penny nails…cigar-box anti-tank mines were filled with dynamite” and every battle station had whisky bottles of Molotov cocktails. They even put a wooden plane decoy on the seaplane ramp. They were as ready as they would ever be with 121 planes, 11 PT boats, 19 submarines guarding all approaches, land mines, booby traps, 5-inch,7-inch and 3-inch guns, caches of food and an emergency supply of fuel. An exciting development was the last minute arrival of six new Grumman TBF torpedo bombers on June 1st. The prevailing attitude: Bring it on.

THE BATTLE OF MIDWAY

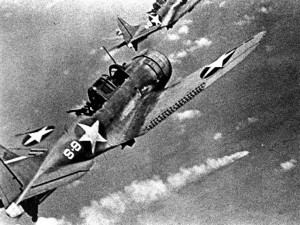

Before dawn on June 4, 1942, the PBYs were searching for the incoming Japanese armada. Marines manned their weapons, pilots and ground crews were waiting for orders. Shortly before 6:00 am one of the PBYs reported they had the main body of the attack force in sight.

In his pillbox on Sand Island, Ed Fox had a .30 caliber water-cooled machine gun. a .30 caliber Browning automatic rifle, a .45 caliber pistol, 50 hand grenades and two rolls of toilet paper. They joked that if they expended all their munitions they sure as heck would need the “TP”. As they ate their cold breakfast, the sirens began to sound.

Elsewhere on Sand Island, Marine Private John Miniclier was climbing the wooden searchlight control tower at his battle station along with non-commissioned officer in charge, Corporal Randolf Hippe. Both wore WW I-type battle helmets so characteristic of the outdated equipment most of the sailors and marines had to work with. He carried the standard-issue 1903 Springfield rifle and some ammo. Being up so high they were able to spot the Japanese planes on their initial approach.

They saw bombs dropping and it looked as if the two of them were right in the pathway of the bombers. One bomb hit a fuel tank nearby. The second hit the laundry building right next to them. They counted around 32 Japanese planes which flew by, their bombs aimed directly at the remaining half of the nearby seaplane hangar which was damaged in the earlier December 7th attack. One enemy plane passed by at eye level, probably assessing damage and later a Japanese Zero flew directly over Miniclier's head. Several buildings on Sand Island and the fuel tanks were set ablaze. Miraculously, the wooden tower they stood on remained standing.

On Eastern Island, the power house was demolished and they lost not only the electricity but the water distillation plant. The Marine Mess Hall was hit and pots and pans went flying everywhere. The regular food supply was destroyed. At the Post Exchange beer cans were catapulted around like shrapnel. Cigarette cartons burst open and packs strewn around. Cigarettes fell like rain on Marines who quickly snapped them up.

The Battle of Midway had begun on land and at sea.

Four days later and six months to the day after Pearl Harbor suffered the surprise Japanese attack, the momentous Battle of Midway came to an end. After the battle one of the guys, who had just sent his clothes to the laundry, went to investigate. “He tried to find his clothes and saw a radio, hanging by its cord, still playing, holes in the roof, and a skivvy shirt on a rafter with his name on it.”

Even war has humor, but in due course that day the reality of the situation set in. Many of the troops felt that because of the enormous amount of firepower the Japanese had, they, as defenders of the atoll, “would have been hurting”. They did not see how they could have survived a land invasion and felt incredibly lucky to have been spared that reality.

Frank Dunlap may have felt that way as well but later that day, June 7, 1942, when he penned a letter to his uncle, he revealed nothing about what he had just been through.

“I am fine as usual and only a bit more tired of this heap of sand than I was the last time I wrote you…. I have now been here over nine months and still there is no sign of relief on the horizon or as to just how long the tour of duty here will be.”

Eventually his tour of duty did come to an end, as did those of his fellow soldiers. They had all experienced things they never had before, made lifelong friends, suffered and rejoiced, made mistakes and had triumphs. How they felt personally and how they handled those experiences varied with each person. Most had loved ones at home. Some never spoke of the war and some healed with the help of fellow soldiers or professionals, although at that time seeking psychiatric help was considered shameful. But, for each, it could be said that Midway had forever changed their lives.

EPILOGUE

GEORGE LEVIN

George Levin, Frank’s artist friend, was reassigned in October of 1943 to Pearl Harbor to help raise the USS California. After that he moved to Moffett Field, California and worked maintaining dirigibles until the end of the war.

George Levin, Frank’s artist friend, was reassigned in October of 1943 to Pearl Harbor to help raise the USS California. After that he moved to Moffett Field, California and worked maintaining dirigibles until the end of the war.

Having graduated before the war with a Masters in Architectural Engineering, he returned to Minneapolis where he was born, for work in his field designing grain elevators and soybean extract plants. In 1949 he opened his own business.

George was introduced by mutual friends to Mary Aberle shortly after his return to Minnesota and they married in 1948. He and Mary had three children: Bill, Katherine and Bob. Mary passed away in 1969.

For the rest of his life, even though he didn’t particularly like rum, George's yearly tradition was to drink a toast every December 7th as he had done with his friend that first time in 1941. When his son Bill was old enough, he joined in the tradition, too.

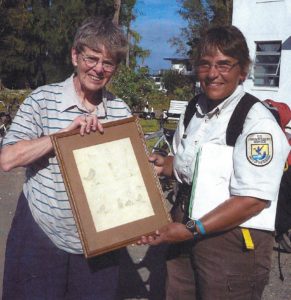

As always, George continued to draw both for business and pleasure. A few lucky friends received holiday cards he created. The gooney bird often appeared in his artwork. He gave the drawing of the life stages of the Laysan albatross to his friend Frank Dunlap. Donated by Frank’s daughter Helen Dunlap, the drawing now hangs in the Midway Atoll Visitors Center.

ED FOX

Ed Fox was transferred to infamous Iwo Jima after Midway. After the atomic bomb was dropped in Japan, he was assigned to the Japanese Occupation and escorted doctors that sought out and treated victims from the blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After the war he took a few months off from military life but soon enlisted into the Army.

He met and married Chris Holman, in 1961, who was teaching military dependents in an American school in Germany. In December of 1962, Chris and Ed welcomed their first child, Mark, in Germany and eventually moved to Springfield, Missouri, where daughter Debbie was born. Chris passed away on October 1, 2019. November 10th, 2019 would have been their 58th wedding anniversary.

Ed has attended the 70th, 75th and 77th Commemorations of the Battle of Midway on Sand Island. He is now 96 and this summer he learned how to snorkel and for the first time, saw what the island he spent so much time patrolling, looked like underwater.

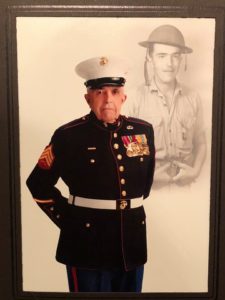

JOHN MINICLIER

Born in Duluth, Minnesota, John Miniclier enlisted in the Marine Corps in August 1940. In September 1941, as a PFC, he and about 1000 other servicemen sailed on the USS Wharton to Midway Atoll where he was stationed on Sand island.

Born in Duluth, Minnesota, John Miniclier enlisted in the Marine Corps in August 1940. In September 1941, as a PFC, he and about 1000 other servicemen sailed on the USS Wharton to Midway Atoll where he was stationed on Sand island.

After the Battle of Midway he earned the rank of Sergeant and was transferred to Eastern Island where he continued searchlight duty.

He stayed on Midway Atoll until he left for the States in 1943. During active duty he served in China, Japan, the Floating Battalion in the Mediterranean, Okinawa, Vietnam and stations in the United States. He retired as a Colonel in May 1975, having served for 35 years.

He and his wife Peg had 4 children. Colonel Miniclier currently lives in Florida with his wife Peg who is also a Retired Marine!

Colonel John F. Miniclier, USMC Retired, returned to the Atoll for the 70th and 75th Commemoration of the Battle of Midway.

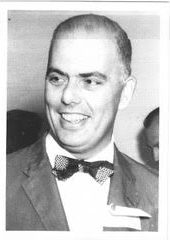

FRANK DUNLAP

After Midway, Frank Dunlap spent two years stationed at Honolulu. In 1944 he was  transferred to Port Hueneme, California where he met his wife, Betty. His last duty station was in Okinawa as a beach commander.

transferred to Port Hueneme, California where he met his wife, Betty. His last duty station was in Okinawa as a beach commander.

Frank returned home in the summer of 1945 and settled in Napa where he and his wife had two daughters, Helen and Mary. He went back to work at his law firm and became a distinguished contributor to his community.

Like many WWII veterans of the Greatest Generation, Frank did not talk much about the war. His only post-war allusion to the event was a lifelong penchant for Aloha Shirts, made by Betty, which he wore whenever he wasn’t in court, and the South Pacific themed wall paper hanging in his office.

He never spoke of Midway other than as home of “the funny bird”. But his respect for nature and stories of the albatross inspired daughter Helen to visit Midway several times and forged a timeless bond between the two of them.

Every year Helen writes her father a Father’s Day letter.

This year, 2019, she wrote: “Midway represents so many things you cared about as I do. The Pacific, wildlife, history, the written word and today as before a critical place to America. Happy Father’s Day. Thanks for sharing your stories…”

Post Script:

A few months after the Battle of Midway, on November 26, 1942, Lieutenant Frank L. Dunlap USMC, received a Letter of Commendation. It said: “For distinguished service in the line of your profession as Communications Officer…during the operations of the U.S. Naval and Marine Forces against the invading Japanese fleet on June 4, 5 and 6, 1942… You directed the operation of all communication and director facilities and were directly responsible for the organization and successful functioning of these units. Your devotion to duty was in keeping with the highest traditions of naval service.” Signed by Rear Admiral D.W Bagley, U.S. Navy

BACKSTORY

One of the Friends of Midway Atoll (FOMA) board members, Helen Dunlap, encouraged this story. Her father, Navy Ensign and Communications Officer Frank Dunlap, was stationed on Midway. Helen sent us copies of his letters and shared some of his stories.

Another Navy Ensign, George Lloyd Levin, entered the Navy as an ensign in June 1941 and by October was stationed on Midway to supervise maintenance of Navy PBY Catalinas.

George knew Frank Dunlap and gave him drawings of Gooney Birds, as the albatross were commonly called then. It is through this drawing that Helen, Frank’s daughter, and Bill, George’s son, recently met via the Internet.

NOTATION

First Lieutenant George Ham Cannon, USMC, was the first U.S. Marine in World War II to receive posthumously the nation's highest military award — the Medal of Honor. He died as a result of wounds sustained in the bombing on December 7, 1941 but before doing so got communications back up and running and saved the lives of others working with him.

REFERENCES

1 From interviews conducted by Connie Toops of four survivors of the BOM (Paul Crook, Donald Drake, John Miniclier and William G. Roy), 2011.

2 Personal communication from William Levin 08/22/2019

3 https://ww2db.com/facility/Midway_Bases/4 Testimony from Bill Brooks, pilot

5 Marines at Midway by Lt. Col. Robert D. Heinl, Jr USMC, 1948

6 Personal letters, military-related papers and information provided by Helen Dunlap, 2019

7 No Right To Win, Ronald Russell, iUniverse Inc, 2006

8 Personal Communication from John Miniclier, 2017

9 Personal communication from Sergeant Ed Fox, 2019

Historical photos from US Navy archives and US Fish and Wildlife Service archives