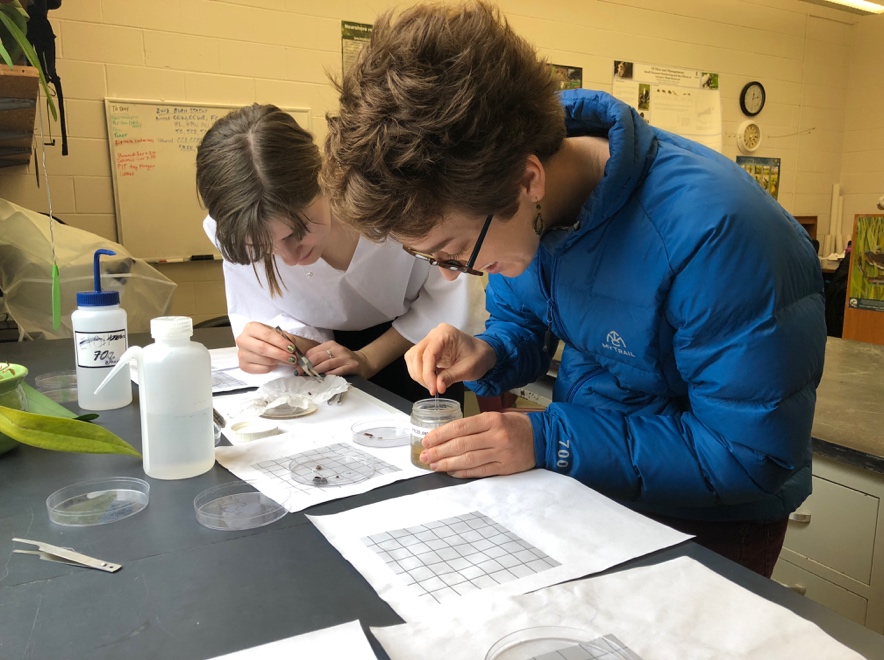

Northern Illinois University and Friends of Midway Atoll Board member Wieteke Holthuijzen have collaborated on exciting research to understand the broader impacts of mice on Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge (Pihemanu, Kuaihelani). In 2015, it was discovered that mice were attacking and killing nesting albatross; in turn, efforts to eradicate mice are now underway.

The questions then arose—what else are mice eating and once mice are gone, how might the ecosystem start to respond and recover?

Arthropods are a major—but often overlooked—part of Midway Atoll ecosystem; this includes everything from spiders, to cockroaches, to ants, to moths, and more. These arthropods play an important role on islands, in particular seabird islands, where they help with nutrient cycling and decomposition.

Black-footed Albatross (Ka'upu) that nest on Midway Atoll, bring in an immense amount of marine nutrients to their breeding colonies. These marine nutrients, which are deposited via seabird guano (poop!) as well as seabird eggshells and carcasses, are very nitrogen-enriched; in turn, these nutrients help wildlife thrive. Arthropods then play a pivotal transition role by breaking down nutrient-rich poop to a form that is available for use by plants—which are then used for nesting and shade by seabirds, or consumed by arthropods, and so forth.

When mice are introduced to islands, their diet tends to be dominated by arthropods—and. because arthropods are key to island ecosystem function, there are lingering questions about how mice impact arthropods and how these arthropod communities recover once invasive mice are eradicated. Midway Atoll provides a “natural lab” where Holthuijzen et al. were able to measure differences in arthropod communities in the presence and absence of mice and predict how arthropod communities might change once mice are gone.

What did they find out?

Even though Sand and Eastern Island are within Midway Atoll and less than a mile apart, their arthropod communities differed substantially from one another. Arthropod communities on Sand Island—where mice are present—were dominated by seabird ticks, earwigs, crickets, and flies. However, on Eastern Island—where mice are not present—there was a very different picture. Ants were incredibly abundant, followed by pseudoscorpions, beetles, and moths. Generally, on islands, mice tend to consume larger and slower-moving arthropods (especially larvae), in particular beetles and moths—and indeed, Holthuijzen et al. found more beetles and moths where mice were absent, possibly indicating a strong impact of mice on arthropod communities on Sand Island.

Here is where the story gets a bit more complicated. Many of the differences in arthropod communities between islands could be due to differences in land-use history. For example, Sand Island has a harbor, whereas Eastern does not and there have been different rates of species introductions to the islands. During the early 20th century, 9,000 tons of topsoil including hundreds of arthropod species were imported from Hawai'i and Guam to Sand Island to create a 3-acre vegetable garden. Sand Island was also the island mainly used for both housing and wartime activities, whereas Eastern Island was largely used for aircraft landing and take-off. So, the increased diversity and more complex arthropod community structure on Sand Island could be a form of “ecological inheritance”.

Therefore, it is critical to consider history of a layered landscape in the context of restoration and conservation. For the published research, visit https://bioone.org/journals/pacific-science/current. This research project is just the start of more exciting scientific inquiry underway on Midway about mice!