By Barbara Carr Whitman

Two resilient and impassioned women, literally worlds apart. Both instinctively guided to a tiny speck of coral sands in the vast expanse of the Pacific.

ʻʻ

One traveled over marble floors through huge museum halls adorned with rich textiles and priceless paintings past glass cases enclosing ancient memories of stone and metal. The other trod soft earthy carpets of leaves through sun-dappled greens and wild splashes of color passing stone and thatch, falling water and ancestral voices.

Puakea Moʻokini-Oliveira and Virginie Ternisien grew up thousands of miles and cultures apart. Virginie was born in France and grew up in a Paris suburb. Puakea was born in Hawaiʻi and grew up on the island of Oʻahu

Both were interested in conservation but of different things.

With two Master degrees in Conservation of Cultural Heritage, Virginie pursued a career in the preservation and restoration of archaeological and historical metal objects. A conservator, she worked mostly behind the scenes in museums and laboratories. She loved the idea of being the first to reveal and see something that no eyes had beheld for centuries if not thousands of years. Likewise, the painstaking and detailed work required for removing layers of sediment and various types of encrustations appealed to her.

Virginie’s native language was, of course, French. But over the years she became fluent in English as the result of school classes, working in Paris with English speakers and frequent trips to the British Isles as an intern. Her available opportunities expanded accordingly and she accepted work in the United States; first in Maryland restoring relics of the Presidio La Bahia, a Spanish fort in Texas, and then in South Carolina helping to restore the H. L. Hunley (1864) a Civil War submarine.

With her schooling behind her, Virginie had more time to spend outdoors. Influenced by her father who grew up on a farm and always kept a vegetable garden, she was happy to find that she had the time and space for a garden of her own. She grew native plants, vegetables, flowers and citrus. She even kept bees. She volunteered at an urban farm and got a certificate in permaculture which, in its simplest form, means natural organic gardening but really entails a much more detailed understanding of natural systems.

She became a long-distance runner and discovered she felt more grounded and connected with nature when she ran. “I would lose myself running on the beach.” But the trash and pollution along the shoreline left her disconcerted. As a result, she became more involved with environmental projects in her community.

These experiences shaped Virginie’s future aspirations that led her into the conservation and protection of wildlife habitats instead of man-made objects. When the opportunity to work on Kure Atoll as a volunteer for the State of Hawaiˋi’s Department of Land and Natural Resources and the Division of Forestry and Wildlife arose, she decided to leave her comfortable life and familiar work with antiquities behind for something entirely different.

Interestingly enough, her next job was on Kure Atoll (Holaniku) which was located within the Papaha̅naumakua̅kea Marine National Monument, which was created by Presidential Proclamation under the authority of the United States Antiquities Act! She spent a year there helping to control invasive plant species, propagating native plants and assisting with biological programs such as shorebird monitoring and banding.

When her assignment was over, she boarded a ship for Honolulu. It made a stop at Midway Atoll (Pihemanu). A few hours and conversations later, Virginie was determined that her next job would be on Pihemanu since it has ecosystems and biological programs are similar to those on Holaniku.

She learned of an available year-long Kupu (which means “to sprout” or “to grow” in Hawaiian) Internship. The Kupu organization’s mission to preserve the land while empowering youth spoke to Virginie and immediately upon returning to her home base in Charleston, South Carolina, she filled out and submitted the application.

Meanwhile in Hawaiʻi, Puakea’s path to Pihemanu was a little more direct. As a youth, she attended Kamehameha Schools. Named after Hawaiian King Kamehameha I, Kamehameha Schools is a forward-thinking and unique private K-12 college preparatory institution that promotes land-based cultural education programs.

Her interest in conservation was nurtured early on as a result of the school’s field trips. She embraced the concept of a deep connection between people, place and culture and had a passion for indigenous and Hawaiian cultural practices as they apply to the natural environment. Puakea enjoyed working outdoors on environmental conservation projects. The more she learned, the more she wanted to know. She didn’t want to specialize in any one thing. She wanted a full understanding of how things in nature connect and interrelate with each other and with humans.

She went on to earn a degree in Environmental Science and upon returning to Hawaiʻi she realized it was her kuleana, “unshakable responsibility” to Mālama ʻ āina. Superficially, that means to take care of the land in a sustainable way. But its real meaning goes much deeper. It is not something you choose but something you feel you must do and it is rooted within the naʻau, or instinctual self/being.

In Puakea’s case, her kuleana is to protect and care for Hawaiʻi's land and culture. No small job. She says, “I feel I am a part of something bigger when I contribute to the conservation not only of our ʻāina (land or place) but also the ways of our lāhui (nation).” She sees herself working in communities preserving traditional ways by learning, preserving and sharing precious knowledge and experience that may have fallen by the wayside.

After college Puakea worked on forest restoration in Hawaiʻi for the Waiʻanae Mountains Watershed Partnership where she learned to monitor and maintain flora in native forests. Participation in Kupu Hawaiʻi’s Summer Youth Conservation Corps allowed her to work for a week each with eight different conservation organizations and she fell in love with “boots on the ground” work.

Puakea’s greatest family influence was her Tutu (grandmother) who had actively been involved in the protection of the northwestern Hawaiian Islands and the passage of the Presidential Proclamation 8031 that created the Papaha̅naumakua̅kea Marine National Monument on July 15, 2006.

She grew up around photos and talk of the islands and her Tutu’s excitement about the subject was contagious. It seemed almost destined that Puakea would land work on Pihemanu. She was just about to accept a paying job where she was already a Kupu intern at the Maui Nui Seabird Recovery Project, when another Kupu Internship in the Conservation Leadership Program on Pihemanu as cropped up. Puakea jumped at the opportunity just as fast as Virginie had.

Which brings us back to the convergence of two paths to Pihemanu and the meeting of two Kupu leaders whose food on Midway Atoll is funded by FOMA.

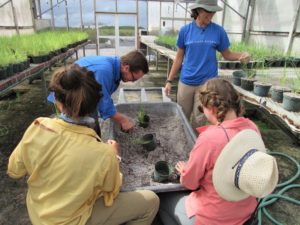

Virginie in-putting field data Planting native grasses Puakea and the volunteers in nursery

Virginie as habitat restoration specialist, is helping return the island to a functional ecosystem that is more conducive to the success and survival of native plant and animal populations. She instructs and guides volunteers that help her with the work. She enjoys working with plants and is involved in the removal of invasive species and propagation and care of native plants. Associated research, such as the pollinator survey, is also a part of her internship.

Puakea is the biological field crew leader but also has the task of nurturing a cultural and environmental program in its infancy. She heads the cultural aspects of the restoration program and also directs, along with Virginie, the daily activities of the volunteers. Both women are deeply involved with designing and implementing the field work. For Puakea, who is of Hawaiian descent, the work has a sense of family and place. She says, “It is like coming to an ancestor’s home to connect on that level as well as to get skills and experience.”

Once a month, Virginie, Puakea, the volunteers and whomever else wants to join, congregate in a room, on the beach or at some other appropriate location for Huliʻia. The purpose of the project, shared by the non-profit organization Nā Maka o Papahānaumakuākea, is to learn enough about a place to properly manage it. Observations are recorded and eventually used in a place-based calendar complete with ʻolelo noʻeau or Hawaiian proverbs.

The meeting is a special time to acknowledge the environment, the changes it may be going through, the creatures of the island and the turquoise and royal blue water around it, the winds that blow over it and the clouds that dot the skies over the vibrant reef boundaries of the atoll. It is also a time for self-reflection.

For Puakea and Virginie, it is a time to relax, get grounded and rest in the knowledge that they are doing everything they possibly can to help save a little piece of paradise and the creatures that call it home, until their two paths, once again, diverge and continue on.

NOTES:

* Kupu, which means “to sprout” or “to grow” in Hawaiian, has a two-fold mission: to preserve the land while empowering youth https://www.kupuhawaii.org/

**On Midway Atoll the Kupu Conservation Leadership Development Program is a cooperative project supported by:

- The Friends of Midway Atoll (FOMA) which pays for the interns’ food, http://friendsofmidway.org/

- US Fish and Wildlife Service that provides the interns’ rooms https://www.fws.gov

- Kupu which provides a stipend for each intern. https://www.kupuhawaii.org/

***Check out Kure Atoll’s Conservancy’s Facebook Post that highlights Virginie’s her personal and extraordinary journey on Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge/Battle of Midway National Memorial at: https://www.facebook.com/search/top/?q=kure%20atoll%20conservancy&epa=SEARCH_BOX