By Barbara Carr Whitman

Sitting together at lunch one day, Marcia Blyth was telling me about a young seal pup she had seen. “At first glance I thought it had a net over its snout”, she laughed, “but it was different.” I was wondering why a net over a seal snout would be funny but knowing Marcia the story would be good. “It looked like sticky strings” she said.

It turns out the seal she was describing was a “weaner”, as weaned seal pups are affectionately called. And like young animals will do, it went nosing around anything that looked interesting. A sand-covered “hairy” sausage-looking thing sitting on the bottom was definitely worth investigating. And it was easy to “catch”.

It is true, sea cucumbers aren’t very fast movers. But imagine the seal’s surprise when something yucky stuck firmly to its snout. Sea cucumbers around the world have a peculiar defensive mechanism. They leave behind body parts as a sacrifice to the predator, s l o w l y move away and regenerate the missing items from the 25% they retain, within a period of days. Some literally drop off two long dill-pickle-slice shaped pieces of their body – one on each side – then quickly close the openings left behind. Others spew their digestive system out of their mouth and some, like the one this seal pup bothered, eject a sticky gooey pile of white strings out of their anus.

Just a little backstory, sea cucumbers breathe through their rear ends. Just inside the anus is a long branching structure of sticky strings called a “respiratory tree”. It was those gooey strings that were stuck to the perplexed animal’s face. It is amusing to think about how surprising that encounter must have been for the young seal.

Before we go further, you need to know that Marcia pronounces her name “MAR seeuh”. She is also from Scotland. I must admit, when we tease her for sounding funny, she suggests perhaps WE sound funny because the English language originated across the pond. Tomayto,tomahto….

Either way, she’s got a great sense of humor and she is often telling us about the seals she sees on her daily patrols around the islands monitoring endangered Hawaiian monk seals as a volunteer for NOAA (National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration) and USFWS (United States Fish and Wildlife Service). This is an unprecedented cooperative program between NOAA and USFWS on Midway and allows NOAA to observe the seals and turtles all year long on Midway rather t han just for two months in the summer as is done on other islands in the Papahanaumakuakea Marine National Monument.

han just for two months in the summer as is done on other islands in the Papahanaumakuakea Marine National Monument.

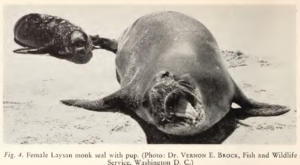

To hear Marcia talk, seals can be pretty funny at times. And, indeed they can be. Except when they aren’t. Everyone knows you never get between a mother and her baby, no matter what the species. It’s the same with seals and a momma seal protecting her pup is a force to be reckoned with. In the water seals are like guided missiles speeding toward a potential threat. On land, you would be amazed how fast they can haul that huge cumbersome body along the sand in defense of their young one. Oh, and have you ever seen those teeth!?

Marcia is well aware of any dangers but she also understands that seals also get nervous and it is easy to unsettle a seal and make it feel uncomfortable enough to escape into the water. This behavior is called “flushing” and Marcia tries to avoid at all costs because it can rob a seal of needed rest, cause a mother to stop nursing or a weaned pup to leave the safety of the beach and it can upset a large resting adult.

Marcia, with blond hair she can sit on, mischievous blue eyes, and dimples in her cheeks like deep impressions in cream, is a hard worker. She walks the sun-baked white beaches daily with a 50-pound pack of equipment, which is almost as tall as she is, and a camera, binoculars and a camel-pack of water on her back which she sips through a connecting tube.

Sometimes when she comes upon a seal or two she has to crouch down with this load and duck-walk further up the beach so as not to disturb the seals. She avoids disturbance wherever possible. In case a seal does become unsettled Marcia records the level of disturbance. Level One: If the seal gestures or vocalizes. Level Two: If it moves more than two body lengths. Level Three: If the seal flushes to the water.

Marcia knows about water. She grew up in Scotland in a small coastal town. Her dad owns and runs a 5-star PADI dive center so she spent a lot of time on boats and in wetsuits. Her mom scubas, too and when Marcia was young her mom would tell her about the creatures she encountered while diving.

Marcia, not surprisingly, became interested in marine biology, and as is typical, she was counselled to choose something else because jobs are competitive and the pay is not very good. She briefly considered studying psychology but instead followed her instinct and is so happy she did.

She has a degree in Conservation Biology and Management. She loves animals (even rescuing five swan-sized ducks when she was 12) and is driven to protect endangered species. She didn’t want to find herself 50 years down the line with regrets. She believes in following her passion, always learning and growing. She understands that if you have a driving passion, you will do well if you follow it relentlessly.

Her job on Midway, as far as seals are concerned, is to help increase the ever-dwindling population of Hawaiian monk seals. There are only about 1400 seals in the main Hawaiian Islands and the Papahanaumakuakea Marine National Monument at the moment and that low number makes them critically endangered. One way to do this is to monitor the current population so scientists can learn more about them and respond quickly to threats, such as disentangling seals or finding young seals in poor physical condition to bring back for rehabilitation.

Once upon a time, between 200,000 and 340,000 Caribbean monk seals plied tropical waters. Both Hawaiian and Caribbean monk seals evolved from the Old World Mediterranean monk seal, also endangered, which still exists in small numbers today. They split from the Mediterranean line (Monachus monachus) 6.5 million years ago and eventually evolved into another genus called Neomonachus.

At that time it was possible to swim between the Caribbean and Pacific through a passage between North and South America. Three or four million years ago, though, the seals were separated into two populations – Caribbean and Hawaiian, when the Isthmus of Panama closed.

Sadly, not seen since 1952, the Caribbean Monk Seal (Neomonachus tropicalis) was Declared Extinct in 2008. Hunting and disease has been blamed for their demise.

If the Hawaiian Monk Seal (Neomonachus schauinslandi) goes extinct, then we will have lost an entire genus of seals. That is why NOAA and folks like Marcia are working hard through beach surveys and other studies to understand the species so the seals can be better protected from threats.

While surveying, Marcia aims to identify each seal she sees, using tags located in the hind flippers. If a seal’s identity is unknown, a minimum of three “identifiers” must be used. These can include scar marks or natural bleach marks on the fur. To do this she usually uses a camera and cautiously takes photographs of the animal so as not to disturb them. She’s developed a keen eye. I was shocked to realize that it is easy to suddenly come upon a 500 pound sand-colored seal sleeping on the beach. I’ve almost walked into them by mistake more than once.

On the day I tagged along, Marcia was looking for one specific “weaner” who was due for her second and last vaccination against morbillivirus (related to canine distemper) that could have a devastating impact on the seal population if an outbreak were to occur. To stave off disease, a seal is given a vaccine; one initial dose and another a few weeks later. There is a time window for the seal to get the second shot, and it was the last day this particular little female could be vaccinated.

Finding a seal in the right position to be vaccinated often takes an enormous amount of waiting or just plain luck. Marcia did find the little female but the seal was stretched out on her back, lazing against a rock. The vaccination must go in the right gluteus muscle. Even if the pup were on her stomach, butt-cheek available, which it wasn’t, the seal was too close to a rock. A seal might respond to the slight “stick” of the needle which, like an epipen shot, takes a fraction of a second. Most of the time, though, a pup doesn't even know it has been vaccinated. It either sleeps through it or sometimes wakes up, goes “huh?” and goes back to sleep. Marcia decided to check on the pup later to avid any risk of injury. As it turns out, the pup was in a good position an hour later and was successfully vaccinated.

Disease is only one of several threats to the seals. The Hawaiian monk seal population has been decreasing for the last 60 years or so due to a variety of factors. Reasons include: low prey availability (primarily affecting young seals), shark predation, disease, entanglement, male seal aggression, habitat loss and other human impacts.

Although seals may breed year-round, most of the pups are born in the spring and summer. Born jet black, the pups nurse for around 40 days. After that, the mom, who has not eaten at all while nursing, is finally able to leave to find food for herself. She never returns to her pup.

Adults often go to the outer reef and beyond to search for fish, mollusks and crustaceans, diving as deep as 1500 feet. But most all of them remain near the island of their birth. They tend to be solitary but adult male-female pairs are often seen resting on beaches during the breeding season. Other adult males may challenge a female’s suitor in a sparring match. I’ve also seen a seal come up on the beach where another one is resting. There is often a little “physical negotiation” and eventually the two settle down near each other.

Near weaning, a pup’s fur gradually changes to silvery gray, molting hair by hair. Weaned pups investigate the shallows near the beach. Unfortunately they occasionally get into sticky situations mouthing different items. Eventually they learn what to catch and how to eat it, too! And they definitely learn to Stay Away From Sea Cucumbers!

For now, life goes on for the Hawaiian Monk Seal. There is great hope that the population will become sustainable. Who knows what the future will bring? There are plenty of good people working to help increase the chances of the survival of not only a species but an entire genus.

As for Marcia, right now she is enjoying her time on Midway Atoll. Her position ends in November 2019 and at some point, she will go back home to Scotland to see family and to decide on next steps after having been a volunteer for 14 months. It is clear the experiences she has had on Midway Atoll have been priceless.

No matter what Marcia decides to do, she will be great at it. She has dedication, spirit, brains, talent, a wicked sense of humor, and a wide and unusual variety of experience and knowledge for her 23 years.